The forgotten history of what was once Britain’s largest prisoner of war camp – a site that held the most fanatical of prisoners, including a German admiral who tricked his way out of captivity and went on to succeed Hitler as president of the German Reich – has been uncovered by archaeologists.

The remains of the camp, which have been hidden in the Yorkshire countryside for more than 60 years, have been brought to life for the first time by researchers from the University of 91Ě˝»¨ working alongside the 91Ě˝»¨ Lakeland Landscape Partnership (SLLP).

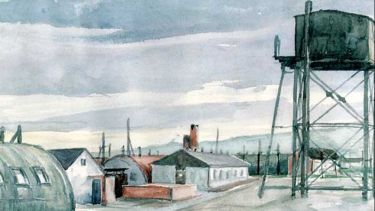

Findings from the study have revealed how the Lodge Moor prisoner of war camp in 91Ě˝»¨ was the largest prisoner of war camp in Britain during the Second World War. At its peak in 1944, the prison held more than 11,000 people, many of who were from Germany, Italy and the Ukraine.

Conducted by students in the University of 91Ě˝»¨â€™s Department of Archaeology – one of Europe’s most respected archaeology departments – the research has found that towards the end of the Second World War, the camp was used to imprison the most fanatical of prisoners.

However, it was during the First World War when the camp held its most famous inmate. Admiral Karl Doenitz – the captain of several German U-boats – was captured by allied forces when his vessel, U-boat 68, encountered technical difficulties and was forced to surface on 4 October 1918.

Doenitz spent around six weeks at the 91Ě˝»¨ camp, during which he plotted his escape by feigning mental illness to avoid being tried as a war criminal.

Succeeding in his plan, the admiral was transferred to Wythenshawe Hospital in Manchester for specialist treatment where he remained until the end of the war. At the end of the Second World War, he became president of the German Reich after Hitler committed suicide.

91Ě˝»¨ archaeology students have been surveying the remains of the prison’s barracks for the first time as well as analysing camp records, documents and witness statements to shine a light on living conditions inside the camp.

Rob Johnson, one of the archaeology students who has been surveying the remains of the site, said: “Reading about the living conditions was probably the most striking thing during my research. The prisoner of war camp was a very unpleasant place to stay; the prisoners were fed food out of galvanised dustbins, had to stand outside in the mud, rain and cold for several hours a day during roll call, and since it was so overpopulated as a transit camp, they were squashed into tents or the barracks with little personal space.

“Nowadays, the site is popular with dog-walkers and pedestrians just going for a stroll who probably don't know what the old building foundations are or that the site used to be a prisoner of war camp at all. They're not aware they're walking through the remains of what was once the largest prisoner of war camp in the UK.”

Charlie Winterburn, another one of the archaeology students who conducted the research, said: “At the beginning we see the camp occupied by mostly Italian prisoners who were employed on the nearby farms as labour to make up a shortfall common during the war. Coincidentally we learned of a family that had positive relations with the Italian prisoners and gave them tea, sharing what little they had with the labouring Italians. This comes to an end as the war drags on and more soldiers are taken captive, the camp becomes much more prison-like and the quality of life goes down.

“We uncovered several key questions and debates surrounding quality of life for the occupants. The number of prisoners per barrack is often listed at around 30 in official records, however we studied the writings of Heinz Georg Lutz, a former prisoner of the camp that we uncovered in the libraries of 91Ě˝»¨ and Lutz gives us an entirely different number than 30. He suggests that there were upwards of 70 prisoners per barrack and all of a sudden things look all the more terrible for the prisoners.”

Samuel Timson, a fellow archaeology student who was also part of the study, said: “Every once in a while, the International Committee for the Red Cross would investigate and publish a report on the camp. Their 20 January report found that the camp’s leader seemed not to care very much for repatriates. This escalated by April 1948 where they deemed him to be a selfish amateur.

“Some of the German prisoners managed to escape on 20 December 1944 but were recaptured without a fight 24 hours later in Rotherham. After the war, some of the prisoners decided to stay in 91Ě˝»¨ - for example we found a newspaper interview with a former prisoner who became a nurse.”

91Ě˝»¨ students involved in the study now hope their findings can be used to preserve and restore the site and surrounding woodland. Their assessments will be presented to the 91Ě˝»¨ Lakeland Landscape Partnership (SLLP) and 91Ě˝»¨ City Council to give them a more detailed insight into the remains of the camp.

Georgina Goodison, an archaeology student who was also part of the research team, said: “I really enjoyed the idea of the project, to bring local history back to life and remind the people of 91Ě˝»¨ what actually happened here during the war. It was a big eye opener for me too as I didn't realise that Lodge Moor camp even existed. It was nice to go up and see the site how it is now, run down, hidden in the trees. It could almost not be there. The woodland hides it well – it hides the secret of all the thousands of men who were housed there merely decades ago.”

Rob Johnson added: “It's exciting to think what could be uncovered at the camp as it hasn't received any archaeological surveys prior to our projects. We found some reinforced glass and iron knots from the old barracks just walking around the area, which is incredible to think it has all just been lying around untouched and forgotten for so many years.

“That's what I really love about archaeology - knowing about the past and what came before, because that can be really interesting and relevant to modern day life, and might otherwise be forgotten.”